Probability Basics

Contents

Probability Basics#

Probability theory is the mathematical framework that allows us to analyze chance events in a logically sound manner. The probability of an event is a number indicating how likely that event will occur.

Note that when we say the probability of a head is \(\frac{1}[2}\), we are not claiming that any sequence of coin tosses will consist of exactly \(50%\) heads. If we toss a fair coin ten times, it would not be surprising to observe \(6\) heads and \(4\) tails, or even \(3\) heads and \(7\) tails. But as we continue to toss the coin over and over again, we expect the long-run frequency of heads to get ever closer to \(50%\). In general, it is important in statistics to understand the distinction between theoretical and empirical quantities. Here, the true (theoretical) probability of a head was \(\frac{1}[2}\), but any realized (empirical) sequence of coin tosses may have more or less than exactly \(50\)% heads.

Common Terminologies#

The sample space is the set of all possible outcomes in the experiment.

For a dice \(\sigma = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}\).

Any subset of \(\sigma\) is a valid event. we can speak of the event \(F\) of rolling a \(4\), \(F = {4}\).

Consider the outcome of a single die roll, and call it \(X\). A reasonable question one might ask is “What is the average value of \(X\)?”. We define this notion of “average” as a weighted sum of outcomes. This is called the expected value, or expectation of \(X\), denoted by \(E(X)\),

\(Weighted Average = \frac{1}{6} * (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6) = 3.5\)

If you play the game \( \infty \) times the average value becomes \(E(X)\)

The variance of a random variable \(X\) is a nonnegative number that summarizes on average how much \(X\) differs from its mean, or expectation. The square root of the variance is called the standard deviation.

\(Var(X) = \frac{(1−3.5)^2+(2−3.5)^2+(3−3.5)^2+(4−3.5)^2+(5−3.5)^2+(6−3.5)^2}{6} = \frac{17.5}{6}\)

Set#

A set, broadly defined, is a collection of objects. In the context of probability theory, we use set notation to specify compound events. For example, we can represent the event “roll an even number” by the set {2, 4, 6}.

Permutation and Combination#

It can be surprisingly difficult to count the number of sequences or sets satisfying certain conditions. This is where Premutation and Combination comes in. For example, consider a bag of marbles in which each marble is a different color. If we draw marbles one at a time from the bag without replacement, how many different ordered sequences (permutations) of the marbles are possible? How many different unordered sets (combinations)?

Permutation(\(AB \neq BA\) , order matters) = \(nPr = \frac{n!}{(n-r)!}\)

Combination(\(AB = BA\) , order does not matter) = \(nCr = \frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}\)

Joint & Conditional Probability#

Joint Probability is the probability of \(2\) independent events occuring : \(P(A \cap B) = P(A)*P(B)\)

Conditional probability tells the probability of \(B\) given \(A\) has occured, it allow us to account for information we have about our system of interest: \(P(B|A) = \frac{P(A \cap B)}{P(A)}\)

If both are same then A and B are independent events.

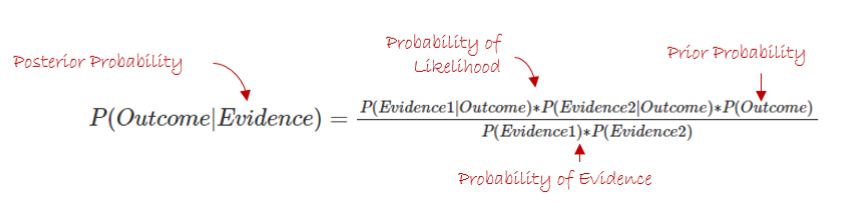

Bayes’ Theorem#

Bayes’ theorem, named after 18th-century British mathematician Thomas Bayes, is a mathematical formula for determining conditional probability. Conditional probability is the likelihood of an outcome occurring, based on a previous outcome occurring.

Fig. 1 Baye’s Theorem#

An easy way of remembering it is using the below example:

What is the probability of a fruit being banana given that it is long, sweet and yellow?

\(P(Banana|Long,Sweet,Yellow) = \frac{P(Long|Banana)*P(Sweet|Banana)*P(Yellow|Banana)*P(Banana)}{P(Long)*P(Sweet)*P(Yellow)}\)

Questions#

Problem: [UBER] Dice in increasing order

We throw 3 dice one by one. What is the probability that we obtain 3 points in strictly increasing order?

Solution:

Suppose we get \(4\) in the first roll then,

Total Probability = \(P(4) * P(5) * P(6) = 1/6 * 1/6 * 1/6 = 1/216\)

Similarly for \(3\), \(P(3) * P(4,5 | 4,6 | 5,6) = 1/6 * (1/36 + 1/36 + 1/36) = 3/216\)

Taking into consideration \(P(1)\) and \(P(2)\) we have the total as \(= 10/216 + 6/216 + 3/216 + 1/216 = 20/216\)

Problem: [LINKEDIN] Cards in increasing order

Imagine a deck of \(500\) cards numbered from \(1\) to \(500\). If all the cards are shuffled randomly and you are asked to pick three cards, one at a time, what’s the probability of each subsequent card being larger than the previous drawn card?

Solution:

It is actually easy to solve this if you think on it a little. Let’s pick any \(3\) cards, now if you rearrange it there will only be \(1\) way in which each subsequent card is larger the previous card. So a total of \(6\) ways to arrange the cards out of which only \(1\) is valid. So the result is \(\frac{1}{6}\).

Problem: [STATE FARM] Cards without replacement

Pull \(2\) cards from a deck without replacement what is probability that both are of different colors.

There can be many variants to this question.

Solution:

Here it is not specified which colour the cards should be - so, they can be either red or black.

The probability that the first card drawn is either red or black is \(1\) since these two are the only possible outcomes.

After the first draw, the total number of cards remaining in the pack is \(51\), out of which \(25\) cards are of the same colour as that of the card that is already drawn. Hence the probability of drawing a card of the same colour as the first one is \(\frac{25}{51}\).

⇒ The probability of drawing two cards of the same colour is \(1*\frac{25}{51}=\frac{25}{51}\).

Another approach to this can be:

Two cards of a particular colour can be drawn in \(C(26,2)\) ways.

⇒ Two cards of either red or black can be drawn in \(2×C(26,2)\) ways.

The total number of ways of drawing any two cards from the pack is \(C(52,2)\).

⇒ The probability of drawing two cards of the same colour is \(\frac{2×C(26,2)}{C(52,2)} = \frac{2×26!}{2!×24!}\frac{2!×50!}{52!}=\frac{25}{51}\)

Problem: [FACEBOOK] N Dice

Suppose you’re playing a dice game. You have 2 die.

What’s the probability of rolling at least one 3?

What’s the probability of rolling at least one 3 given N die?

Solution:

P(at least 1 three) \(=\) P(exactly 1 three) \(+\) P(2 three) \(= 1/6 * 5/6 + 5/6 * 1/6 + 1/36 = 11/36\)

The second part of the question is a little tricky, let’s start by generalizing the above equation:

P(at least 1 three) \(= 2*(5^1/6^2) + 5^0/6^2\)

Now for N dice: P(at least 1 three) \(=\) P(exactly 1 three) \(+\) P(2 three) \(+\) P(3 three) … \(+\) P(N three)

Combining both \(= N * \frac{5^{N-1}}{6^N} + N * \frac{5^{N-2}}{6^N} + N * \frac{5^{N-3}}{6^N} + ... + N * \frac{5^0}{6^N} = \frac{N}{6^N}(5^{N-1} + 5^{N-2} + .. + 1)\)

Problem: [FACEBOOK] 3 Zebras

Three zebras are chilling in the desert. Suddenly a lion attacks.

Each zebra is sitting on a corner of an equally length triangle. Each zebra randomly picks a direction and only runs along the outline of the triangle to either edge of the triangle.

What is the probability that none of the zebras collide?

Solution:

Each zebra has 2 options of travel: clockwise or anticlockwise. So a total of \(2*2*2 = 8\) options.

Out of this only way in which they donot collide is if all of them travel clockwise or anticlockwise. So a total of \(2\).

Therefore the probability of no collision \(= 2/8 = 25%\)

Problem: [POSTMATES] Four Person Elevator

There are four people on the ground floor of a building that has five levels not including the ground floor. They all get into the same elevator.

If each person is equally likely to get on any floor and they leave independently of each other, what is the probability that no two passengers will get off at the same floor?

Solution:

The number of ways to assigning five floors to four different people is to get the total sample space. In this case it would be \(5 * 5 * 5 * 5\).

The number of ways to assign five floors to four people without repetition of floors is \(5 * 4 * 3 * 2\) because for the first passenger you have five different options. The second person has four, and so on. Note that this number counts all possible orders between passengers as well.

The result is then \(\frac{5 * 4 * 3 * 2}{5 * 5 * 5 * 5} = 0.192\)

Problem: [AMAZON] Found Item

Amazon has a warehouse system where items on the website are located at different distribution centers across a city. Let’s say in one example city, the probability that a specific item X at location A is 0.6, and at location B the probability is 0.8.

Given you’re a customer in this example city and the items are only found on the website if they exist in the distribution centers, what is the probability that the item X would be found on Amazon’s website?

Solution:

Probability of the item being present= \(1-\) p(item NOT in A AND NOT in B) \(= 1-(0.4*0.2)=0.92\)

Problem: [SPOTIFY] Max Dice Roll

A fair die is rolled \(n\) times. What is the probability that the largest number rolled is \(r\), for each \(r\) in \(1..6\)?

Solution:

If \(r(1≤r≤6)\) is the largest number you have allowed for your \(n\) rolls, then you forbid any number larger than \(r\). That is, you forbid \(6−r\) values. The probability that your single roll does not show any of these \(6−r\) values is \(\frac{6−r}{6}\) and the probability that this happens each time during a series of \(n\) rolls is the obviously \((\frac{6−r}{6})^n\)

There is a subtle nuance to this problem, in the above solution we have assumed the \(max<=r\) which is different from \(max=r\) or in other words if \(r=3\), the above solution gives results for \(r= 1,2,3\). The solution of \(r=3\) is a little more involved:

Let’s take \(r=3\), for \(n\) die rolls we should have atleast one \(r\). The Probability of that is:

Problem: [FACEBOOK] Labeling Content

Facebook has a content team that labels pieces of content on the platform as spam or not spam. \(90%\) of them are diligent raters and will label \(20%\) of the content as spam and \(80%\) as non-spam. The remaining \(10%\) are non-diligent raters and will label \(0%\) of the content as spam and \(100%\) as non-spam. Assume the pieces of content are labeled independently from one another, for every rater. Given that a rater has labeled \(4\) pieces of content as good, what is the probability that they are a diligent rater?

Solution:

This can be solved using Baye’s theorem:

Not Spam = \(NS\)

Spam = \(S\)

Diligent =\(D\)

NotDiligent =\(ND\)

\(P(D|NS, NS, NS, NS) = \frac{P(NS, NS, NS, NS|D)*P(D)}{P(NS, NS, NS, NS|D)*P(D)+P(NS, NS, NS, NS|ND)*P(ND)}\) \(P(D|NS, NS, NS, NS) = \frac{0.8^4*0.9}{0.8^4*0.9+1^4*0.1}\) = ~\(0.787\)

Problem: [FACEBOOK] Raining

You are about to get on a plane to Seattle. You want to know if you should bring an umbrella. You call \(3\) random friends of yours who live there and ask each independently if it’s raining. Each of your friends has a \(2/3\) chance of telling you the truth and a \(1/3\) chance of messing with you by lying. All \(3\) friends tell you that “Yes” it is raining.

What is the probability that it’s actually raining in Seattle?

Solution:

Even though the problem is straightforward one can interpret the problem in many ways. Taking a Bayesian approach is probably appropriate in a real world sense, but if you are told by the interviewer you have no ability to determine the priors, you can’t use Bayesian. Check this thread for a detailed discussion on this problem.

For it to be not raining, all friends must be lying. Therefore, the solution must be the inverse of the probability that all three are “messing with you.” \((1/3)*(1/3)*(1/3)=1/27\) (3.7% chance they are all lying).

Since there is only a \(3.7%\) chance all three friends are messing with you, there is a \(96.3%\) chance it is raining.

Problem: [MICROSOFT] First to Six

Amy and Brad take turns in rolling a fair six-sided die. Whoever rolls a \(6\) first wins the game. Amy starts by rolling first.

What’s the probability that Amy wins?

Solution:

Amy can win on the first roll, third roll, fifth roll, and so on.

Probability of Amy winning in the first roll = P(six rolled by her) = \(1/6\)

Probability of Amy winning in the third roll = P(six NOT rolled by her in first try) * P(six NOT rolled by Brad in first try) * P(six rolled by her in 2nd try) = \((5/6) * (5/6) * (1/6) = 1/6 * (5/6)^2\)

Similarly, the probability of Amy winning in the fifth roll = \((1/6) * (5/6)^4\)

Similarly, the probability of Amy winning in the seventh roll = \((1/6) * (5/6)^6\)

Hence, total probability of Amy winning = Sum of all such events = \((1/6) + (1/6 * (5/6)^2) + (1/6 * (5/6)^4) + (1/6 * (5/6)^6) + ...\)

The sum of such an infinite Geometric Progression series is = \(\frac{a}{1-r} = (1/6) / (1 - 25/36) = (1/6) / (11/36) = 6/11\)

Hence, probability of Amy winning in any of her turns = \(6/11\)

Problem: [GOOGLE][FACEBOOK] Double Sided Coin

A jar has \(1000\) coins, of which \(999\) are fair and \(1\) is double headed. Pick a coin at random, and toss it \(10\) times. Given that you see \(10\) heads, what is the probability that the next toss of that coin is also a head?

Solution:

There are two ways of choosing the coin. One is to pick a fair coin and the other is to pick the one with two heads.

Probability of selecting fair coin \(= 999/1000 = 0.999\)

Probability of selecting unfair coin \(= 1/1000 = 0.001\)

Selecting \(10\) heads in a row = Selecting fair coin * Getting 10 heads + Selecting an unfair coin

P (A) \(= 0.999 * (1/2)^5 = 0.999 * (1/1024) = 0.000976\)

P (B) \(= 0.001 * 1 = 0.001\)

P( A / A + B ) \(= 0.000976 / (0.000976 + 0.001) = 0.4939\)

P( B / A + B ) \(= 0.001 / 0.001976 = 0.5061\)

Probability of selecting another head \(= P(A/A+B) * 0.5 + P(B/A+B) * 1 = 0.4939 * 0.5 + 0.5061 = 0.7531\)

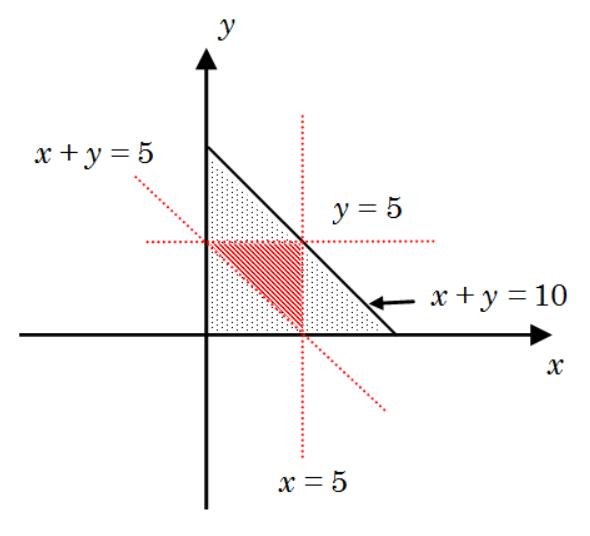

Problem: [GOOGLE] Forming a triangle

A 10 feet pole is randomly cut into 3 pieces. What is the probability that exactly form a triangle?

Solution:

Suppose the pole is \(AB\) and there are two points \(P\) and \(Q\) such that \(AP = x\) and \(PQ = y\), so that \(QB = 10 – x – y\) as we know that sum of two sides of a triangle is greater than the 3rd side. Hence

\(x + y > (10 – x – y)\) or \(x + y > 5\)

\(y + (10 – x – y) > x\) or \(x < 5\)

\((10 – x – y) > y\) or \(y < 5\)

Also we know that, all the parts of pole must be greater than \(0\),

or \(x > 0, y > 0, 10 – x – y > 0 or x > 0, y > 0, x + y < 10\)

Plotting the lines \(x + y = 10 x + y = 5, x = 5, y = 5\). Now favorable area is the area of the middle red shaded triangle.

Required probability \(= 1/4\)

Problem: [LYFT] Flips until two heads

What is the expected number of coin flips needed to get two consecutive heads?

Solution:

Let’s first assume \(x\) is the expected number of coin flips required for getting two heads in a row. Now:

If the first flip turns out to be tail you need \(x\) more flips since the events are independent. Probability of the event \(1/2\). Since \(1\) flip was wasted total number of flips required \((1+x)\).

If the first flip becomes head, but the second one is tail(\(HT\)) - \(2\) flips are wasted, here total number flips required would be \((2+x)\). Probability of \(HT\) out of \(HH, HT, TH, TT\) is \((1/4)\)

The best case, the first two flips turn out to be heads both(\(HH\)). Probability, \(1/4\) i.e. \(HH\) out of \(HH, HT, TH, TT\). No of flips required \(2\).

So from the above scenarios, \(x = 1/2(1+x) + 1/4(2+x) + (1/4 )* 2\) \(= 1/2 [ (1+x) + 1/2(2+x) + 1 ]\) \(= 1/2 [ 1 + x + 1 + x/2 + 1 ]\)

\(x / 4 = 3/2\) \(x = 6\)

So the expected number of flips would be \(6\)

Problem: [LYFT] Number of cards before an ace

How many cards would you expect to draw from a standard deck before seeing the first ace?

Solution:

Let \(X\) represent the number of cards that are turned up to produce the \(1^{st}\) ace. For this problem, we cannot apply the Geometric Distribution because cards are sampled without replacement.

Instead, we begin by considering the probabilities of drawing the \(1^{st}\) ace on the \(1^{st}\) card, \(2^{nd}\) card, and so on:

\(P(1^{st} card)= \frac{4}{52}\)

\(P(2^{nd} card)= \frac{48}{52}\frac{4}{51}\)

\(P(3^{rd} card)= \frac{48}{52}\frac{47}{51}\frac{4}{50}\)

\(P(n^{th} card)= 4* \frac{48!}{(49-x)!}\frac{(52-x)!}{(52)!}\)

With this we can calculate the average number of cards by applying the definition of expected value:

\(E[X]= \sum\limits_{x=1}^{52} 4x \frac{48!}{(49-x)!}\frac{(52-x)!}{(52)!} = \frac{53}{5} = 10.6\)

Problem: [FACEBOOK] Ad Raters

Let’s say we use people to rate ads.

There are two types of raters. Random and independent from our point of view:

80% of raters are careful and they rate an ad as good (60% chance) or bad (40% chance). 20% of raters are lazy and they rate every ad as good (100% chance).

Suppose we have 100 raters each rating one ad independently. What’s the expected number of good ads?

Now suppose we have 1 rater rating 100 ads. What’s the expected number of good ads?

Suppose we have 1 ad, rated as bad. What’s the probability the rater was lazy?

Solution:

100 raters are divided into 2 groups according to probabilities:

\(20\) lazy raters: \(100%\) good ads -> \(20\) good ads; \(80\) careful raters: \(60%\) good ads -> \(80 * 0.6 = 48\) good ads. Total \(68\) good ads.

There could be 2 cases:

Random rater is careful with probability of \(0.8: 0.8 * 0.6 = 0.48\) - probability or rating good ad Random rater is lazy with probability of \(0.2: 0.2 * 1 = 0.2\) - probability or rating good ad Total probability of rating ad as good is \(0.48+0.2 = 0.68\). The expected amount of good rates \(100*0.68 = 68\).

It’s \(0\) probability that the rater is lazy because lazy raters always rate ads as good.